Untangling Rosie’s History at America’s Most Unusual National Park

The words “Experimental” and “National Park” don’t normally go together, but they do at the Rosie the Riveter WWII Home Front National Historical Park, (1414 Harbour Way S., Richmond, CA; 510-232-5050; NPS.Gov/RORI/Index.htm) a place not quite like any other national park or historical monument.

Part of what makes the park so unique is the sheer number and scope of storylines being explored. Go to the Grand Canyon, for example, and you’ll probably learn about the forces of nature that created the canyon.

Go to Richmond, California’s National Historical Park, though, and you’ll hear many stories told. The role of women in WWII, Henry J. Kaiser’s massive shipbuilding operation, and an unprecedented mass African-American migration from the South to the San Francisco Bay Area are just three of the major threads treated there.

Another thing that makes the park unique is that it is more or less without boundaries. Historical sites having to do with the East Bay’s contribution to the war effort are scattered all over the city of Richmond, and include the Craneway Pavilion, which was then a factory producing jeeps and tanks; the SS Red Oak Victory, a victory-class cargo ship assembled at the city’s Kaiser Shipyards; and the moving Rosie the Riveter Memorial at Marina Bay Park.

How, then, to get a handle on all this scattered history? An excellent way is to book a bus tour. Twice a month, usually on a Wednesday morning, 2.5 hour tours stop at most of the city’s wartime sites, and pass through neighborhoods where much of the massive labor force required to make ships and tanks lived.

Tours are narrated by the remarkable Betty Reid Soskin, at 92 the oldest active park ranger in the United States. Describing her that way, though, makes her sound like a novelty act when in reality she is as sharp and vigorous as a woman a generation younger.

Longevity seems to run in the family. Betty’s mother lived to be 101, and a great-grandmother made it to 102. That great-grandmother, incidentally, was born into slavery in 1846 and survived into Betty’s late twenties – meaning that if you take the bus tour, you are in the presence of someone who has had an adult conversation with someone who could remember where she was when she heard the Emancipation Proclamation.

Next Stop: 1943

Some stops on the bus tour have a lot to look at. You don’t board the SS Red Oak Victory, for example, but you can walk right up to its mooring and imagine the enormous Whirley crane next to it loading munitions bound for the Pacific theater. And at the Rosie the Riveter Memorial, there’s plenty of time to read quotes from real-life Rosies set into cement on a path laid out to be exactly as long as the ships many helped put together.

At some stops, there’s nothing left to see, and here’s where the scope of Betty’s historical perspective really comes into play. She has the bus stop, for example, at a tough block in the infamous Iron Triangle neighborhood to point out streets where housing for ship workers once stood. Richmond’s population ballooned during the war from 20,000 to 130,000, she tells us, with virtually all the newcomers employed at the shipyards or in some other part of the war effort. Huge numbers of houses and apartments were hastily constructed in the early 1940s to handle the influx.

At the end of the war, however, most jobs disappeared even more quickly than they had been created. Housing units were removed from the sale and rental markets, and in some cases, were bulldozed with only a few days’ notice.

It’s a sad bit of history to contemplate, the idea of 80,000 idled workers hitting the streets with nothing to do and no place to go. But like any good historian, Betty makes a link between the past and present. She makes a sweeping gesture to indicate the bleak street we are on, with its empty lots, aimless young men, and a high crime rate. It’s Betty’s firm belief that when a whole community suffers an injustice the way Richmond’s workforce did 70 years ago, the pain does not quickly dissipate. It festers and lingers, and manifests itself in the elevated levels of desperate crime found in the Iron Triangle today. “People may not even know why they’re angry anymore, but they still feel it,” she says simply.

Betty knows something about rage, and injustice. She was born in 1921 in Louisiana. When she was six, her family lost everything when the city of New Orleans deliberately dynamited several levees in an attempt to divert floodwaters away from the city, deluging the Soskins’ low-lying, mostly African-American neighborhood. Starting from scratch, the family relocated to East Oakland.

Betty also knows something about the East Bay home front. She was 20 and living in Berkeley when the United States entered WWII. She got a job working at a union hall in Richmond. A young woman showing up every day to do her bit for the war effort exactly fits my idea of the classic Rosie the Riveter experience, and I can’t wait to hear what Betty has to say about the exhibits at the visitor center, which is the pick-up and drop-off point for the bus tour.

Visitor Center

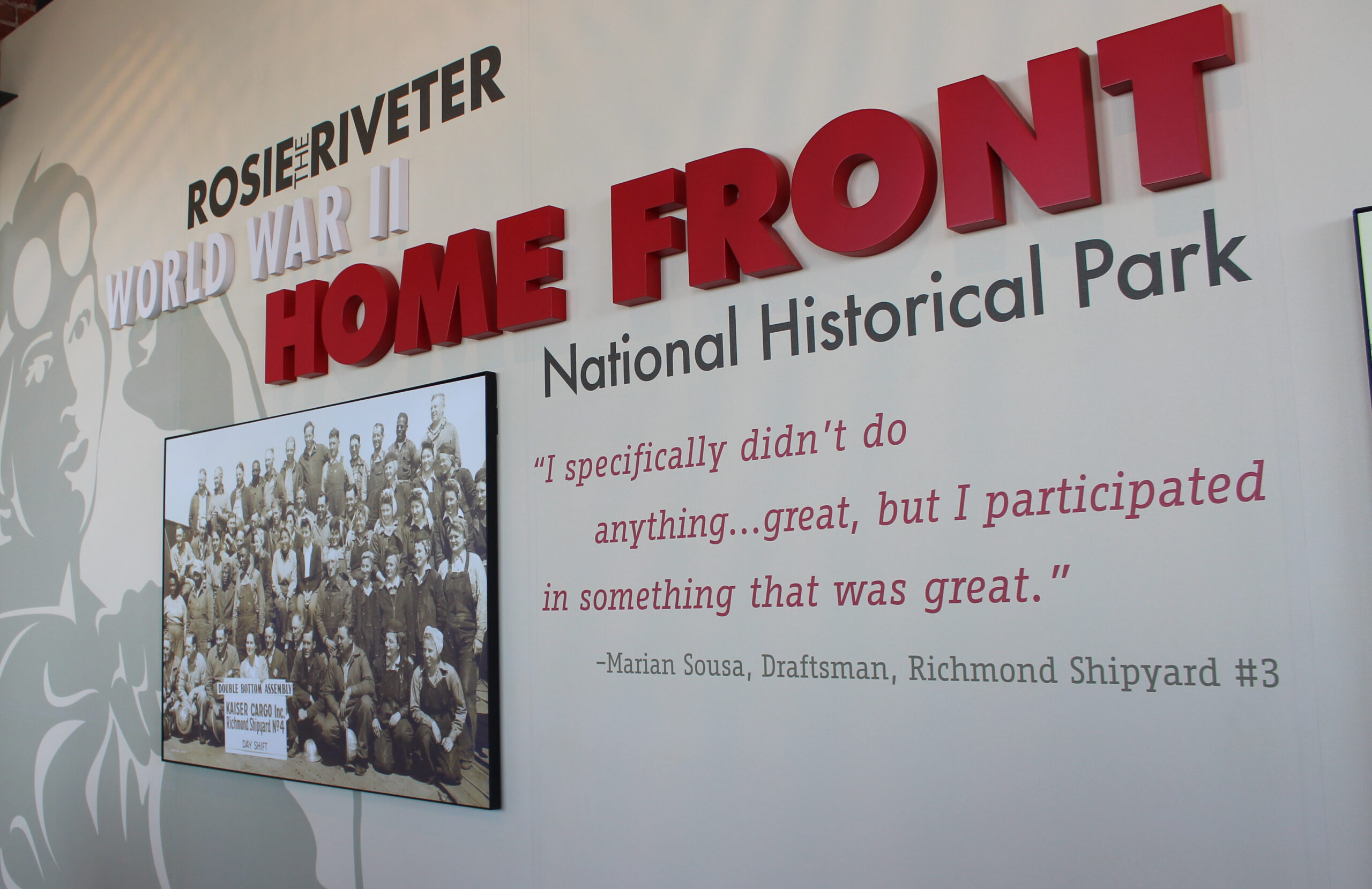

For all its eccentricities, one thing the Rosie the Riveter WWII Home Front National Historical Park does have in common with other parks is a visitor center. It’s a compact little museum with a very manageable number of exhibits telling the story of Richmond’s role in the war. I listen to a recording of one of F.D.R.’s fireside chats, watch a time-lapse video of a victory ship being assembled over the course of 30 days, and view a number of storyboards detailing the entry of tens of thousands of women into the wartime workforce.

During my visit, I’m lucky enough to make the acquaintance of a tiny but energetic elderly visitor named Annette Vanderslice. I spot her cheerfully trying her hand at a replica of a riveting gun, and she seems to be enjoying the noisy toy so much that I impulsively ask if she herself is a former Rosie.

She explains that at a few days short of 86 years old, she isn’t quite old enough to have had such an adult job during the war. But she shares still-vivid memories of helping other kids in her San Francisco neighborhood to pull a wagon full of collected scrap metal — “cigarette cartons were the best, because they had tin foil inside,” she enthuses — because in those days even students felt like they needed to contribute. It’s a short encounter, but it reminds me that there can be much more to a museum experience than the exhibits themselves. (It also reminds me of how perilously close we are to losing first-person accounts of the era, if people who were children then are elderly now.)

In the small downstairs theater, I watch a 20-minute short film called Home Front Heroes. In it, many women and a few men who worked at the Kaiser shipyards, mostly as welders, reminisce about the war. They relate that it was hard at first, barely knowing how to hold a hammer and having only a sketchy understanding of what welding and riveting even were. But they all emphasize the positive, relating how the male workers eventually came to respect the work of the women, and pointing to the accomplishments of the Richmond workers: 747 liberty and victory ships slid down the ways during the four years ships were constructed on the shores of the San Francisco Bay. “It was,” says one former worker, “The most wonderful coming-together of the American people I’ve ever seen.”

Afterward, having seen the exhibits and the film, spoken with someone who was there, and visited the historical sites, I feel like I have a pretty good understanding of the WWII home front experience.

Right?

“Well, that’s a white woman’s story,” Betty tells us. She has reappeared in the theater after the film to talk one last time to the bus-tour group. She is speaking without judgment or accusation; she’s simply making the point that her wartime experience was different from that of most of the movie’s interviewees. Betty spent the war as a clerk, sorting 3×5 cards in an all-Black auxiliary of the segregated Boilermaker’s Union. (Unions at the time were under no legal obligation to integrate.) Working in an inland part of the city, she never saw a ship under construction with her own eyes. She also never saw what she was doing as remarkable, because many of the women she knew worked outside the home — few African-Americans of the time could afford to live on a single income.

Betty confesses that the first time she saw Home Front Heroes, she wasn’t sure she liked it. She explains that there was a time in her life when she would have regarded the film’s more effusive statements about togetherness as “hogwash.”

But, she quickly adds, two things have happened to her over the course of her 92 years. One is that, as she says, “I have outlived my rage.”

The second is that she has become comfortable with what she calls “conflicting truths.” One woman speaks of harmony and social progress, another other sees business as usual … and maybe both are right. Betty has come to believe that there can be, and in fact, probably should be a place where both women’s truths can exist side by side.

And that is what the Rosie the Riveter WWII Home Front National Historical Park is: a complex, walk-in history lesson. It’s a monument without boundaries, and a museum that exists as much “under the hats of the interpreters” (as Betty puts it) as it does in the actual exhibits.

And it’s a place where you can hear different, even conflicting accounts of history and draw your own conclusions about it. This shades-of-gray, think-for-yourself approach may, in the end, be the most remarkable thing about this unusual national park.

Planning Your Trip

Betty is a force of nature and reason enough to visit the Rosie the Riveter WWII Home Front National Historical Park. For the fullest experience, try to catch one of her Wednesday morning bus tours. They’re very popular, and fill up well in advance. Make a reservation by calling 510-232-5050 x 0, and be prepared to reserve a date as much as six months in the future.

If you can’t make that work for you, you can try to catch one of her 45-minute ranger talks, which include the film Home Front Heroes. She speaks at 12:30 p.m. on Wednesdays and 2 p.m. on Tuesdays and Saturdays. These talks are, like the bus tours and the museum itself, completely free.

Of course, Betty is not the only voice of the park. Most Thursdays at 2 p.m., Flora Ninomiya talks about her experiences in an internment camp for Japanese-Americans, and on Fridays, a group of real-life Rosies gather to informally chat with the public about their wartime experiences.

Ranger talks cover a number of other topics, as well. Before you visit, be sure to know what’s scheduled by checking the web site at NPS.Gov/RORI/PlanYourVisit/Things2do.htm#CP_JUMP_565086.

To book your San Francisco Bay Area vacation, contact Heather Cassell at Girls That Roam Travel at Travel Advisors of Los Gatos at 408-354-6531 at or .

To contract an original article, purchase reprints or become a media partner, contact ">editor [@] girlsthatroam [.] com.