A Small Gallery At The Oregon History Society Tells A Compelling Story About The Rose And How It Came To Symbolize Portland

by Heather Cassell

The roses hadn’t bloomed when I visited Portland earlier this spring. They were still cut back, their thorns glistening in the rain as I walked through the International Rose Test Garden in Washington Park.

I had a vague understanding of how Portland became the “City of Roses,” from a tour I took with Evergreen Escapes years ago, but I didn’t quite grasp the meaning or that it went well beyond Mrs. Georgiana Pittock, whose prized roses still bloom at the Pittock Mansion in the West Hills on the other side of West Burnside and the park on Pittock Drive. The mansion has a dazzling view of Portland, the Willamette River, and the Cascade Mountains that surround and cross through the city from its grounds, which are filled with Georgiana’s well plotted and manicured roses.

It’s understandable why anyone would think that Georgiana was the one-woman powerhouse behind roses being Portland’s hallmark and that she was crowned as “Queen of Portland’s Roses,” but she wasn’t the only person who shape the city’s image with the soft pink petal and later the hundreds of varietals developed and grown throughout the city.

Little did she know that she not only established the nation’s first rose society and rose show but created a legacy that has endured for 130 years and defines the city her husband and she loved so much.

The story of how Portland became the City of Roses is an exciting one and a sad one all at the same time. It’s a story about a city that came together multiple times around a single rose and perhaps a story about one of the first successful city tourism campaigns in history as a city redefined and branded itself.

For The Love Of Roses

Touring the Oregon Historical Society Museum I came across a small gallery on the bottom floor with the “Madame Caroline Testout: The Rose that Made Portland Famous” exhibit. It was here that a whole new side of the story about how roses became the pride of Portland, what became of the legendary rose that is the city’s symbol, and the woman whose namesake is the rose while escaping the rain for a couple of hours recently.

There’s no doubt that Georgiana had a vision and strong follow through to bring roses to Portland. It was the age of roses: The Victorian era and others were similarly enthusiastic about the fragrant flower, especially long after Georgiana passed away and roses fell out of fashion by the 1920s.

Georgiana’s love of the flower took her to England to see the roses for herself. She was inspired by a lecture at the Unitarian church near her home at Pittock Block in what is today’s Pearl District on the edge of Downtown Portland, years before she moved into the mansion, I discovered in the exhibit.

An adventurer and society lady married to Henry L. Pittock, publisher of the Oregonian and a financier, she traveled to London to see the rose shows. It was there she realized Portland would be an ideal place for similar shows. Immediately upon her return to Portland, she set up an informal gathering asking her friends to show off their best roses in her backyard in 1888.

That gathering was the forerunner to the first official rose show not only in Portland, but the United States and the launch of the first rose society in the United States, the Portland Rose Society in 1889. By February 1902, the city’s rose society was fully established with its own charter and membership and the Rose Show adopted the rules and guidelines of the National Rose Society of England, today known as the Royal National Rose Society Gardens.

The royal rose society, which was formed in 1876 and is the world’s oldest specialized plant society with a worldwide membership, shuttered its doors due to financial struggles May 15, 2017, reported the BBC. It has been in administration for the past year. An informal group, The Rose Society, with no association to the royal rose society has taken up the cause of England’s roses, according to the group’s website.

Portland’s Rose Society continues stronger than ever.

The spring of 1889 marked the first-ever official rose show in the US. The show was held at the Assembly Hall of Bishop Scott Academy under the auspices of the Trinity Episcopal Church Ladies Guild on May 21, 1889, according to the museum.

Campaign Rose City

The show was a success. The movement was on.

Portland wanted to change its image from Stumptown to Rose City and it did that through a massive tourism and advertising campaign. It started with a World’s Fair-type event, the Lewis and Clark Exposition. Portlanders were inspired by the city’s success at the World Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, according to the museum.

The Lewis and Clark Exposition commemorated the centennial expedition from St. Louis, Missouri to the mouth of the Columbia River in Astoria, Oregon in 1905.

To beautify the industrial and logging port city, it was proposed to line the streets with roses. A rose lover, Frederick V. Holman suggested the rose varietal favored by Madame Caroline Testout, an elegant pink flower, that had her namesake. The rose created by Jean Pernet-Ducher was originally known as the La France, I read in the exhibit.

The beautiful pink rose was immediately embraced by the entire city. By 1905, Portland’s streets were lined with neatly manicured hedges with blossoming roses, most notably, the Madame Caroline Testout rose.

Frederick also suggested to city officials to nickname Portland the “Rose City” at the exposition.

At the exposition, Portlanders outdid themselves at that year’s Rose Show. Organizers expected 100,000 roses from 15,000 home rose gardens, but 400,000 roses greeted visitors, according to the museum. The most loved rose was the Caroline Testout rose.

About 2.5 million people traveled to the exposition in less than five months due to a massive tourism public relations campaign, according to the museum.

People fell in love with Portland and its roses. By the end of the exposition, the city became unofficially known as the “Rose City” and Mayor Harry Lane proposed the annual Rose Festival.

Portland’s city leaders didn’t officially adopt the city’s nickname the “City of Roses” until 2003 when the city’s council declared it with a resolution. A copy was on display at the exhibit.

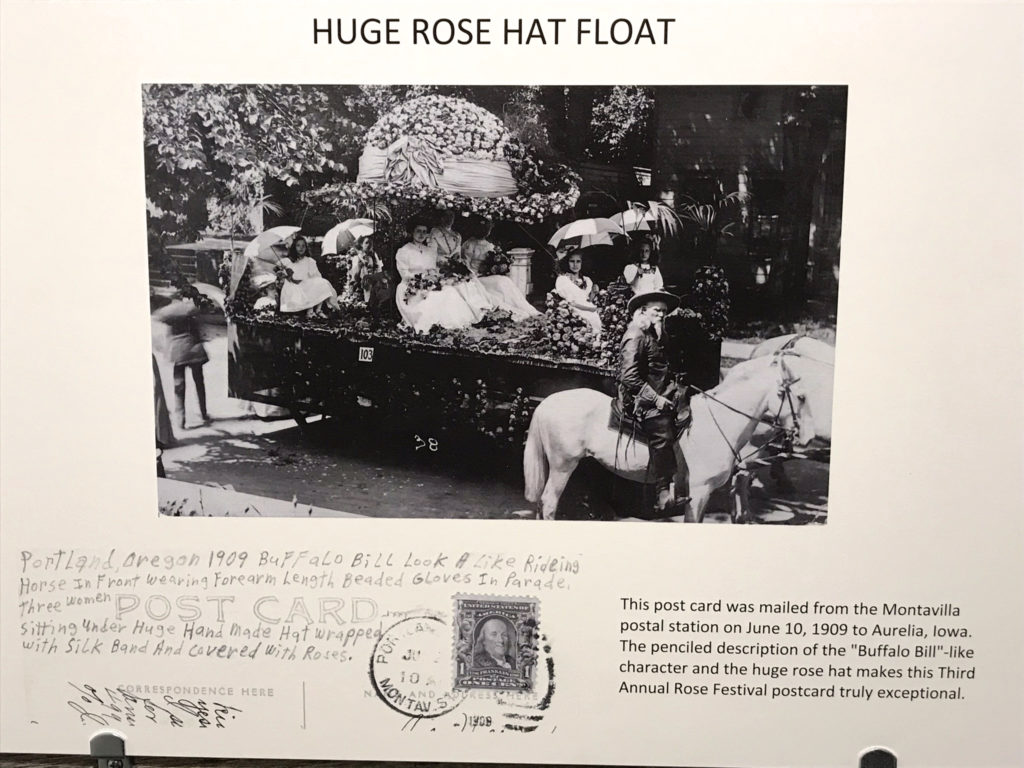

In 1907, the annual Rose Festival began with roses from home gardens decorated floats and hats and other events.

Branding The Rose City

Residents and businesses embraced the name and soon there were logos and store names with “Rose City” in them throughout Portland.

The city’s promotional campaign continued in 1912 when the Royal Rosarians were formed with 100 members who pledged to promote the festival and Portland’s roses.

The Rosarians followed British rule establishing a monarchy with a parliament to govern the society and annually voting on a queen and a king at the Rose Festival Parade.

The city’s brand ambassadors traveled across the US promoting Portland and its roses.

I was surprised, but not surprised that Portland’s rose and the society that developed around it had such influence. Portland’s rose spread like wildfire from the Pacific Northwest down the California coast to Oakland and Santa Barbara.

The rose’s popularity also stretched across the US to the White House’s first rose garden planted by Mrs. Woodrow Wilson in 1913. Of course, the garden included a Caroline Testout rose bush.

The festival and the Caroline Testout rose inspired other rose gardens, societies, and festivals throughout the US.

Who is Caroline?

Despite the rose bearing Caroline’s name, little is known about the woman behind the rose.

Authors writing about the popularity of roses during the late 19th and early 20th century believe that Caroline was a French dressmaker and businesswoman who used the roses to market her London dressmaking shop, Madame Caroline. The rose attracted clientele, society women loved the roses, according to authors.

Historians at the museum noted that they haven’t been able to verify the connection between Caroline the dressmaker and businesswoman and the rose that bears her namesake, according to a panel toward the end of the exhibit.

It appeared the rose eclipsed the woman, but the rose also faded through the years in Portland.

After World War I, the rose fell out of fashion and the hedges were neglected or torn up to plant something else in its place. Jesse A. Currey, who established the city’s International Rose Test Garde in Washington Park and well established in Portland and America’s rose societies, championed Portland’s rose-lined streets until his death in 1927. Today, it’s difficult to find a Caroline Testout rose in the city, according to the museum.

The rose faced tough competition. It was no longer the bell of the ball as newer varietals began to be tested and other trends or priorities took precedence. That could partially be attributed to Europe’s roses being brought to Portland to protect them from The Great War, which cemented Portland’s brand as the Rose City. However, the relationship between the World War I and Portland wasn’t touched upon in the exhibit.

Despite that flaw, the exhibit, for its size, was well curated and focused on the important facts and artifacts that gave rise to Portland’s adoption of the rose as it’s mascot.

The exhibit dived deep enough to provide a sense of admiration and understanding without being overwhelming. It was enough to wet people’s appetites for those who want to learn more about the city’s history and the popularity of rose shows in the US. It was a nice educational experience for those who were there simply to gain some understanding and insight about the rose that made the City of Roses.

I particularly found it fascinating as an example of an early successful city branding and tourism campaign that is one of the blueprints similarly city campaigns today. Something that I wasn’t aware of before my experience at the museum.

If you are a rose lover and attending the Rose Festival and Rose Show, which started this weekend and runs through June 10, I highly recommend catching this exhibit before it closes June 17.

THE GAZE:

Oregon Historical Society Museum, 1200 Southwest Park Avenue, Portland, Oregon 97205. 503-222-1741. ohs.org.

EXHIBIT DATES: Now through June 17.

TYPE OF EVENT: Museum, Exhibit

RATING: 3 = Aqua

(0 being the worst rating and 5 being the best rating)

VIBE: Shhhh. It’s a museum.

SCENE: Casual

SERVICE: You are on your own after your ticket or pass is scanned. No one invited me to join the lecture that was happening or to explain what was happening at the museum that I must see.

DAZZLE ME AGAIN: I was impressed with the exhibits, particularly with Portland’s rose, the civil rights movement, and Oregon University. The information provided was thought-provoking and well organized and displayed.

WHERE TO NEXT?: These exhibits were specific to Oregon and the state’s historical society.

THE TICKET: $ = Under $10

(price of an average ticket for an individual to enter the event)

WORTH THE OUTTING?: My mind was expanded.

Book your next Portland adventure with Girls That Roam Travel. Contact Heather Cassell at Girls That Roam Travel at 415-517-7239 or at .

Full Disclosure: Girls That Roam visited the Oregon Historical Society as a guest of Travel Portland.

To contract an original article, purchase reprints or become a media partner, contact .