A Powerful Small Exhibit Tells the Story of the Impact of Portland’s Black Power Movement

by Heather Cassell

The Civil Rights Movement touched nearly every corner of the United States during mid-century America: Portland, Oregon was no exception.

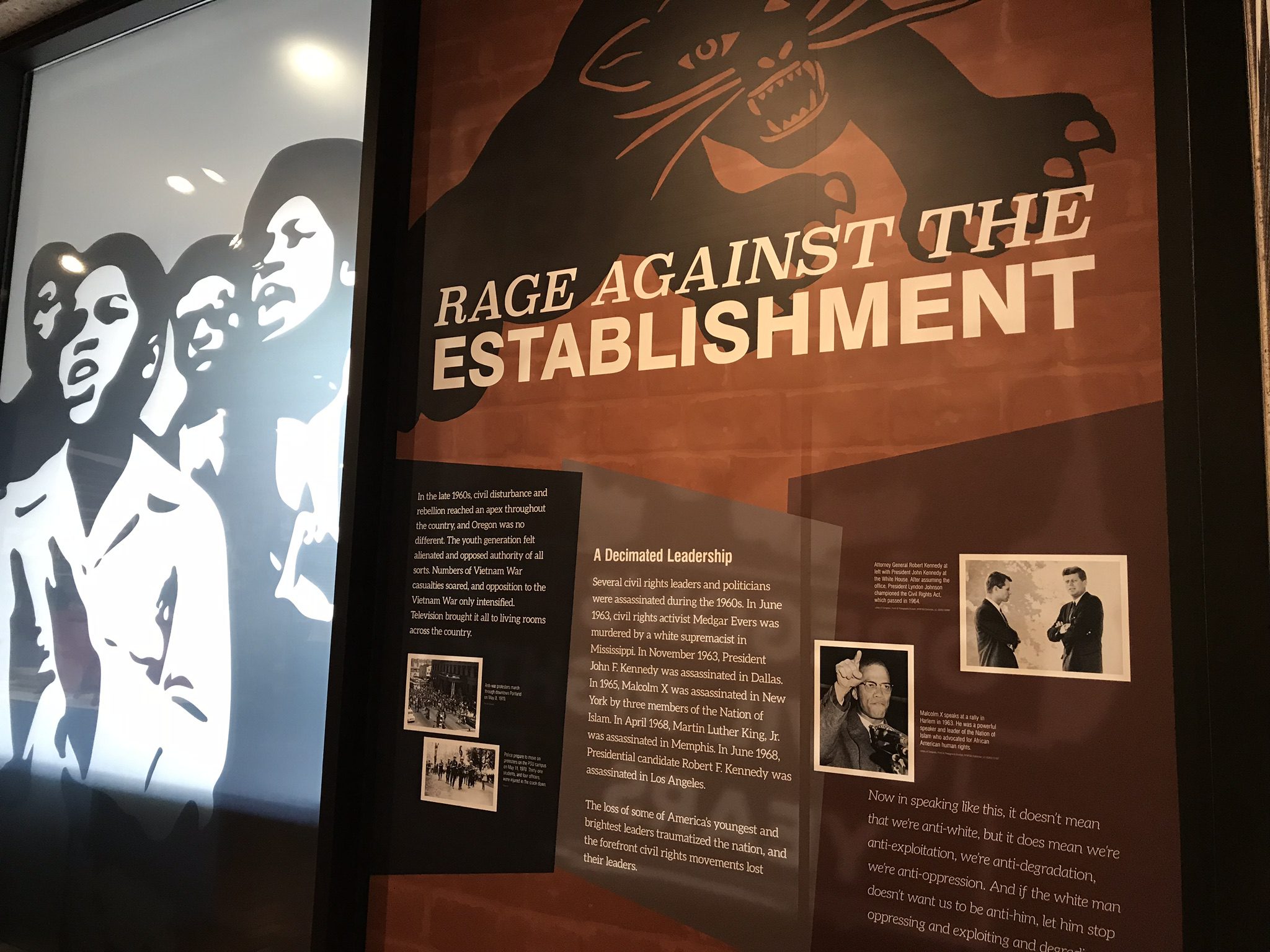

The Rose City’s small Black community, nearly 800 households strong at the time, raged against the establishment grabbing at the promise of the Civil Rights Movement after a century of oppression in the Oregon Historical Society’s exhibit, “Racing to Change: Oregon’s Civil Rights Years.”

The exhibit powerfully captures Black Portlanders’ experience during 30 years of tremendous social change when the Civil Rights and Black Power movements came to Oregon.

Black Portlanders drove the movements in the Pacific Northwest.

The exhibit, presented by the Oregon Black Pioneers, opened in January and runs through June 2018.

The Oregon Trail to Racism

The history, of course, was a century in the making. Racism came to Oregon with its white settlers nearly 100 years before the Civil Rights and the Black Power movements took root.

Many Black settlers came to Oregon with their former slave owners.

They found themselves emancipated 3-years after they resettled in the Oregon territory.

The territory outlawed slavery in 1844.

Three years after resettling in the Pacific Northwest territory, the former slave owners were required by law to set their Black slaves free.

At the time, the territory stretched from the Pacific Ocean to the Rocky Mountains.

After the deadline, Blacks were considered free, but not free to be in Oregon.

The “Peter Burnett Lash Law,” also known as the “Lash Law,” also passed in the territory’s constitution in 1844, set out to brutally punish Blacks who stayed within Oregon’s borders beyond 2-years for men and 3-years for women.

The laws passed, 15 years shy of Oregon becoming a part of the union, on February 14, 1859. Oregon was the only state to enter the union with an exclusionary law, according to African American historians.

The law was never enforced, but it kept the population white.

It was repealed in 1926, but the language remained on the books until Oregon voters removed it in 2002, reported Oregon Public Broadcasting.

The law and many others that came after it banned Blacks and other people of color from owning property, creating contracts, citizenship, voting, interracially marrying, segregated schools, and where they could live from the mid-1800s into the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

“To fully understand the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s it is not enough to study the individuals and events of those two decades—it is also necessary to study the civil wrongs practiced by the dominant culture in the many generations before the movement occurred that made it necessary,” Dr. Darrell Millner, professor emeritus at Portland State University and former department chair of Black Studies, said in a quote in the exhibit.

The history leading up to Portland’s Civil Rights Movement was not included in the small but mighty exhibit.

Portland’s Black Rose

The exhibit started with the birth of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s and progressed through the Black Power Movement into the late 1970s.

It flowed from the events that led to the tipping point, with the Albina Riots in 1967 and 1969, and followed the rise of Black Oregonians, a majority Portlanders, as some Black Portlanders gained key leadership positions on local school boards, unions, and elected local and state office.

The riots happened in Albina, Portland’s Black neighborhood.

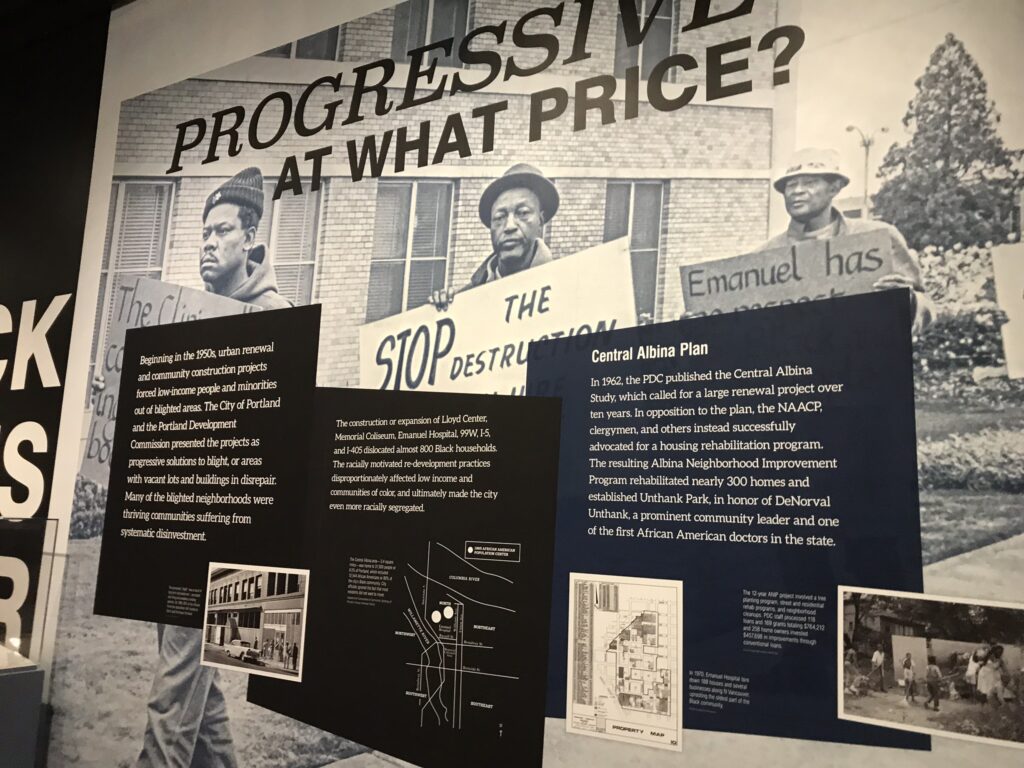

The neighborhood developed after nearly 800 Black Portlander households were displace from downtown due to an “urban renewal” project to revive the so-called “blighted area,” in the 1950s when in reality it was the city’s “systematic disinvestment” at play.

Black Portlanders were relocated to Albina, a North and Northeast neighborhood in the city.

Despite, being segregated from Portland by the Willamette River’s natural divide and later the erection of three major largescale buildings and freeways, that cut the community off from the rest of Portland, the Black Portlanders built their community.

Media and police ignored the fact that Albina was a bustling neighborhood with its businesses and community. Instead, the neighborhood was labeled as a “ghetto” by the media and police heavily patrolled the parks and streets.

“Where else but Albina do cops hang around the streets and parks all day like plantation overseers? Just their presence antagonizes us. We feel like we are being watched all of the time,” The Oregonian quoted an unnamed youth in the exhibit.

This was especially true when about 100 Black Portlanders gathered at one of the neighborhood’s parks, Irvine Park, in anticipation of hearing Black Panther Party Minister of Information Eldridge Cleaver speak. Police circled the park in the already overly-policed neighborhood in anticipation of a riot, one of the panels explained.

They got their riot when Eldridge did not show, one of the event’s speakers used rhetoric to incite violence, and some youths threw rocks at a nearby store window and assaulted a white park employee. Suddenly, centuries of unrest erupted into rage.

The night of rage caused $50,000 of damage and police arrested 115 people, according to BlackPast.org.

Two years later, confrontations between young Black Portlanders and police were more violent during a weekend of unrest.

The incident happened outside popular hangout spot Lidio’s Drive-In, June 13, 1969. Youths threw bottles and firebombs, assaulted drivers and police officers, and vandalized property. Civil unrest was high that summer, more than 150 cities across the country experienced violent demonstration that summer.

The Portland police report sent to Oregon Governor Tom McCall on June 18, 1969, described an incident where an officer was striking a Black youth several times while two police officers held the youth’s arms and another officer with a machine gun observed “calling the Black youths obscene names.”

Governor Tom defended the officers in his response to the report writing that an inquiry with state employees stated the incidents where police officers responded, “too vigorously to a situation,” may have been “isolated” and that they “exercised restraint and conducted themselves in a proper fashion,” according to the two documents that were displayed.

The governor also wrote, “Under no circumstances can we condone violence on the part of adults or youth, black (sic) or white.”

Dozens of people were arrested by the end of the weekend. The riots caused thousands of dollars in damage.

The violent clashes could easily have been inserted into the modern day, like the riots that erupted after the police killing of Black teenager Michael Brown in 2014, proving that racism and police brutality remains an unresolved problem in America.

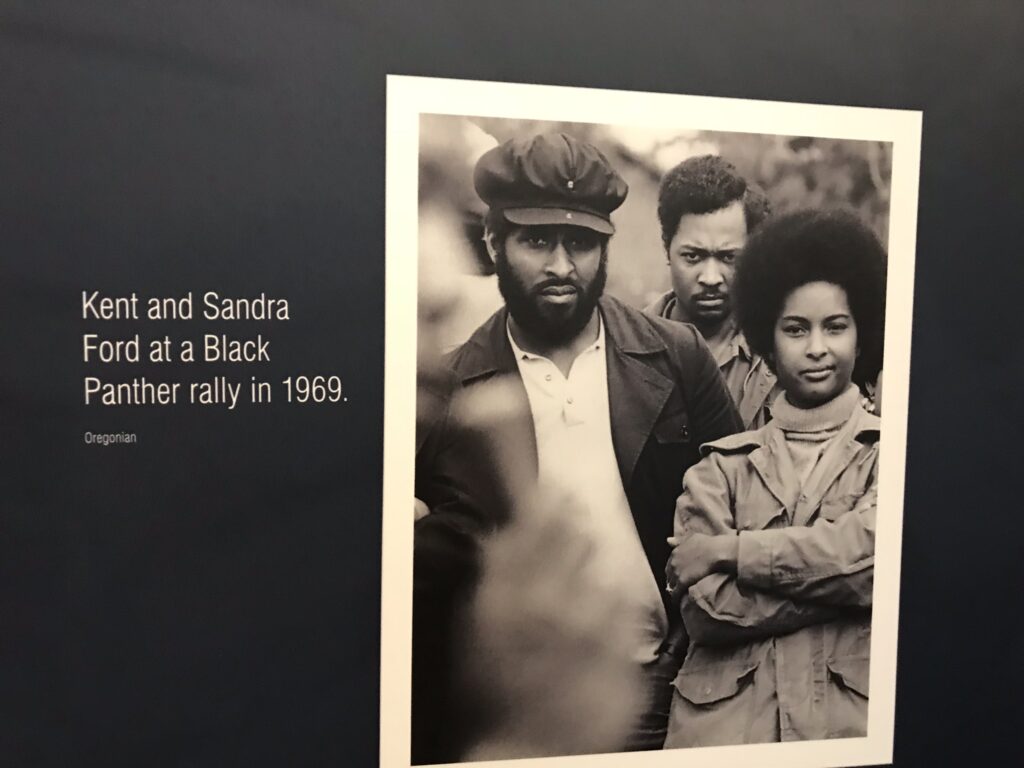

Black Portlanders Kent Ford and Percy Hampton responded to the violence by forming a Black Panther Party chapter in Portland. It was one of 40 throughout the United States, two of which were in Oregon. Eugene also had a chapter.

“If they keep coming in with these fascist tactics, we’re going to defend ourselves,” said Kent, quoted in one of the panels.

FBI and local police heavily surveilled members of Portland’s Black Panther Party and spread anti-Black Power rhetoric stating the party was a Black Ku Klux Klan and its members were anti-white people. Authorities and the media used the party’s “militant rhetoric” in recruitment tactics against them and portrayed the party and its members as being involved in criminal activity.

It was further from the truth, the Eugene chapter, a panel explained, set up lunch programs for kids and taught African American history.

Kent’s wife, Sandra Ford, was also politically active in the party and led protests.

Breakthrough

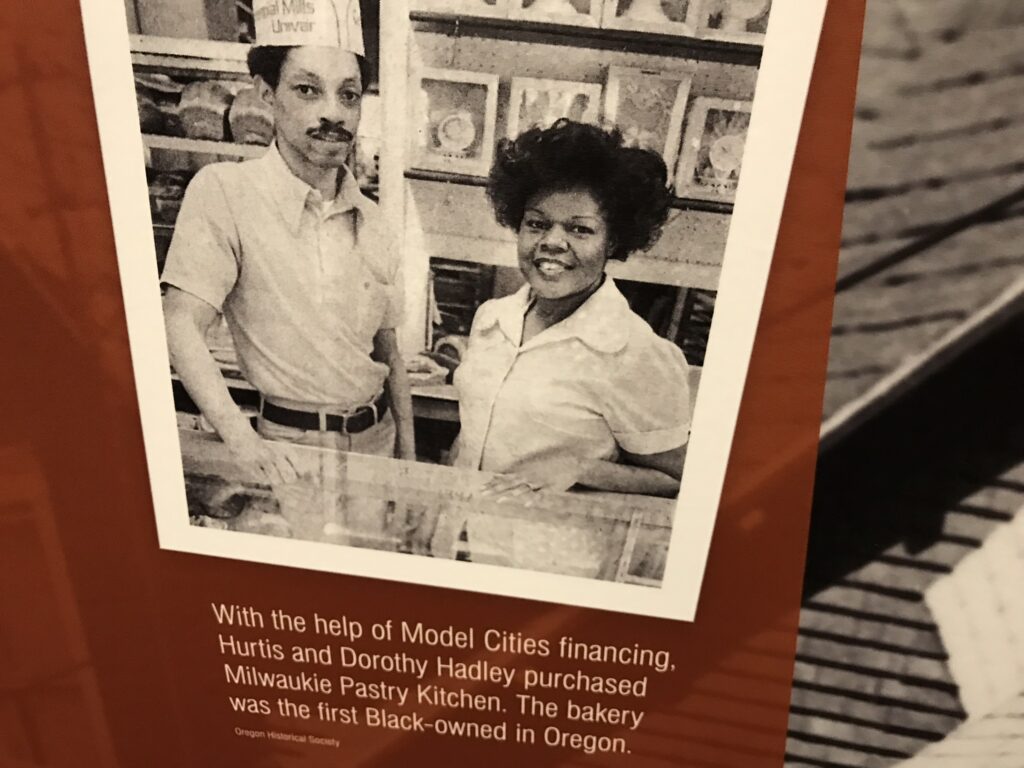

The community’s resilience and desire to thrive under the weight of racism that attempted to block any progress at any instance found a crack in the system by the mid-20th century.

The Civil Rights Movement brought breakthroughs from desegregation of the Rose City’s schools to Black students’ successful protests and sit-ins to establish Black student unions and African American Studies at Portland State University and Reed College, both located in the city.

Portland’s Civil Rights Movement was a century-long hard journey pushing to overturn racist laws with little movement until the mid-1950s. Black Oregonian men’s fight for suffrage displayed the community’s resilience against all odds.

Black people were not allowed to vote starting in 1857 when it was banned in the state’s constitution. The community attempted four times to repeal the law but failed. The law was not repealed until 1927 when the law granted Black and Chinese men the right to vote in the state. Chinese men had also been legally banned to vote.

Oregon’s small Black community fought back attempting to gain suffrage starting in 1857. They failed three more times before the act was repealed in 1927 granting Black and Chinese men the right to vote in the state.

The fight for the vote and displacement demonstrated the community’s resilience.

The movement caught fire in the 1950s. Armed with Supreme Court decisions, such as Brown v. Board of Education, that desegregated schools. The community’s own push for change with the help of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People’s legal challenges also targeted desegregation in Portland’s schools, the exhibit depicted.

It took another 15 years before Portland’s school district got its first African American member of the school board, Gladys McCoy in 1970. Gladys was one half of Portland’s Black political power couple. Her husband, William McCoy became the first-ever Black state legislature in 1972. He was elected Oregon State Senator after serving only one term.

The well curated exhibit was packed with historical moments and key people covering a span of topics from student demonstrations to business and civic leadership to the Black Arts Movement.

It is an amazing exhibit complimented by lectures about Oregon’s African American history that should not be missed when visiting Portland.

Beyond the exhibit, the Oregon Historical Society should be on your travel itinerary.

THE GAZE:

“Racing to Change: Oregon’s Civil Rights Years,” Oregon Historical Society, 1200 Southwest Park Avenue, Portland, Oregon 97205. 503-222-1741. ohs.org.

TYPE OF EVENT: Exhibit

RATING: 4

(0 being the worst rating and 5 being the best rating)

VIBE: Thought provoking. Prepare for a leisurely stroll with many pauses.

SCENE: Casual and relaxed, with multiple floors of exhibits to wander through and learn about Oregon and Portland’s history.

SERVICE: This is a self-guided exploration through multiple exhibits on several floors. The staff is helpful and there is a lot of information available upon entering the building.

DAZZLE ME AGAIN: The exhibit was amazing, but it was not the only one that was incredible. Every room I went into with different shows drew me in and held my interest from beginning to end. I would definitely visit the Oregon Historical Society again.

WHERE TO NEXT?: The exhibit is now available virtually at the society’s website.

THE TICKET: $ = Under $10

WORTH THE OUTTING?: This was a rock’n good time!

Book your next romantic getaway to the Caribbean with Girls That Roam Travel. Contact Heather Cassell at Girls That Roam Travel at 415-517-7239 or at trips@girlsthatroam.com.

To contract an original article, purchase reprints or become a media partner, contact editor@girlsthatroam.com.