Three Women’s Response to 2020’s Racial Reckoning Is Spreading Black Joy and Pride by Celebrating The Women of The Black Panther Party In A Mural and The Party in A Museum.

by Heather Cassell

Black joy and pride radiate out from the two-story house on the corner of Center Street and Dr. Huey P. Newton Way in West Oakland.

It is what Jilchristina “Jil” Vest, the homeowner, envisioned during 2020’s tumultuous racial reckoning that erupted in the United States and spread like wildfire around the world.

She brought the Women of the Black Panther Party Mural and the Mini Black Panther Museum to life rallying her friends Lisbet Tellefsen and her partner former Black Panther Party member Ericka Huggins, and the community.

I wanted to create something, “where you can cry tears of joy, which heal you, versus tears of rage, which is what we were all doing last summer. I want that for myself, and I also wanted it for my community, and I wanted it for Oakland,” Jil said about the 30-foot mural depicting women of the Black Panther Party on the street-facing side of her house.

Inspired by the “Say her Name” movement, 2020’s racial reckoning, and living in the Black Panther Party’s birthplace, Jil wanted to bring visibility to the women of the Black Panther Party and show the community what it could and did do for itself using the Panthers as an example.

The mural was created using photographs taken by Stephen Shames, who widely photographed the Panthers. Oakland muralist Rachel Wolfe-Goldsmith compiled the images of Black women working in the Panther’s community survival programs in the four panels across the street-facing wall on the side of her house.

For the first time ever, the names of the 260 Black Panther women are memorialized in the mural.

“We wanted people to look at the mural and stand stronger, stand taller, put your shoulders back, and say, ‘Those are my people. Those are my ancestors,'” Jil, a 54-year-old Black queer activist, said about the mural.

Black Joy and Pride

That’s what visitors get, Black joy when they see the mural and museum, Jil said.

“And maybe they can feel a little free for the moment,” added Ericka, 73, who is Jil’s mentor on the project.

An estimated 1,000 people have viewed the mural since its unveiling February 14, according to Jil.

“People [have] been coming from across the country to see the mural,” she said, but then they would just leave.

Four months after the mural was unveiled, the museum opened June 19 (Juneteenth).

“There is so much more that they should have been interacting with and now they can they go to the mural [and] they go to the museum … it’s more meaningful,” said Jil, who estimated that more than 500 people have visited the museum since its opening as of July.

The museum, which is only open on weekends, has been sold out since its June opening.

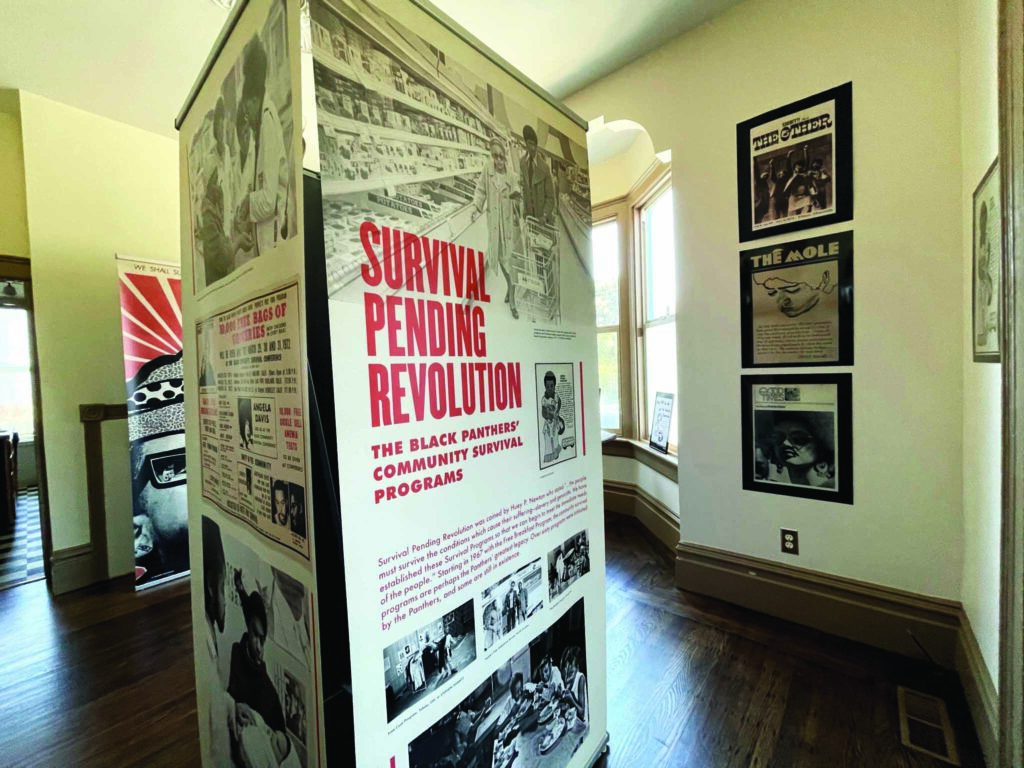

The small museum holds a lot of history in its overview of the Black Panther Party that spans three rooms and 16 years on about 16 panels along with other artifacts, Lisbet a 60-year-old Black lesbian community archivist and publisher who loaned the panels to the museum, said. Much of that history is not often taught.

Perhaps one of the most remarkable features of the exhibit is its focus on women. From the mural outside to the moment you step into the first room, it is mostly about the women who created and sustained the community survival programs and made up 70% of the Black Panther Party.

The women and their work are all beautifully displayed on pop-up panels that were originally created by Lisbet for a restorative justice conference tied to the Panthers’ 50th anniversary in 2016 produced by Fania Davis Jordan. Fania’s sister is Black lesbian activist Angela Davis, one of the more prominent female members of the Black Panthers.

It took nearly a year to create the mural, which she commissioned for more than $100,000 using small individual donations and community grants, Jil said.

The museum came four months later.

Currently, the museum is supported through Jil’s own donation of the vacant apartment and the panels that Lisbet happily pulled out of storage when Jil called her about creating the museum in the downstairs apartment of her house.

Jil’s tenants moved out in January. Around that time, a woman admiring the mural as Rachel painted asked her if there was a museum inside.

Jil lives on the top floor of the house.

The Black Panthers

For most of my life, I held a negative view of the Black Panther Party. My perspective was one based on fear propagated by the American government’s campaign against the party and the images encapsulated by the media that ended up in my history textbooks and repeated by some of my own family members.

The Panther’s community programs “tend to get lost behind the historical laziness, which just distills them down to angry Black men with guns who had good fashion sense,” said Lisbet, who is an activist.

The Black Panther Party grew out of Oakland in 1966. The organization ran more than 60 community survival programs throughout the U.S. and abroad until it dissolved in 1982.

The first time I encountered a radically different narrative of the Black Panther Party was in Portland, Oregon. I was at the Oregon Historical Society, which featured, “Racing to Change: Oregon’s Civil Rights Years,” an exhibit presented by the Oregon Black Pioneers in 2018.

The exhibit told the story about the Black Panther’s community programs in Portland and Eugene, such as Eugene’s children’s free breakfast program, and the rallies against over-policing in the community and other racial issues in Portland as a part of the Pacific Northwest state’s broader Civil Rights Movement.

In Oakland last month, Ericka nodded her head, softly saying, “yes,” as we walked through the exhibit together retelling what I learned at the Oregon exhibit and listening to her stories being in the heart of the movement.

Ericka, who was the director of the Oakland Community School for nearly 10 years, one of the Black Panther Party’s programs, explained to me the evolution of the many different community survival programs was organic. They sprouted out of community members identifying and expressing needs within the community displayed on the pop-up panels with explanations of how they operated and benefited the community.

The programs addressed nearly every aspect and necessity of life and grew out of a grassroots movement. Women who needed childcare to work and participate in the movement. Educating and nourishing children at schools so they could learn. Providing free ambulance services and health clinics to conducting health care research to figure out their own health issues. The research led to groundbreaking discoveries, such as sickle cell anemia, which predominantly impacts Black and Mediterranean communities. It became the first sickle cell anemia research and education program nationwide, Ericka said. Senior programs where people volunteered to help older people safely buy and bring their groceries home, take them to doctor’s visits, get and take their medicines, prepared meals, to checking in on them and keeping them company.

The images and Ericka’s stories about the Panthers and the work they did profoundly moved me as we walked from display to display. Many of her Panther friends have since died, she noted.

One of Ericka’s proudest days at the school, she said pointing to another picture next to the one with her and the school’s staff and teachers, was when Civil Rights icon Rosa Parks made an unexpected visit.

“We didn’t ask for her to visit. She called to ask, ‘May I please come see your school dear?’” said Ericka who was thrilled by the opportunity. That memory and pride resonated decades later as she told me the story about the students performing a play for Rosa and the one child who never left Rosa’s side. “It was one of the happiest days of my life.”

The Black Panther’s Impact

The programs were replicated throughout the United States and in other countries, she noted.

The first chapters outside of Oakland emerged in Portland and Seattle and the movement continued to grow from there.

“Seattle was the first chapter, after Oregon … there were 45 or more chapters in the United States but also internationally,” Ericka said noting indigenous people in New Zealand and in India were inspired to follow the Panther’s example protecting and building better communities for themselves by reading their newspapers.

Ericka noted that the Panthers weren’t made up of only Black people. The Panthers built coalitions with other underrepresented communities.

“We were the first organization to form coalitions with all of the other organizations, including the white organizations, like The Young Patriots and the White Panthers,” Ericka said pointing to the photo of an Asian American woman who taught at her school.

Word about the museum and the photo of the Asian American woman alongside her peers got to that woman.

Ericka opened the visitor’s book where guests have left messages. She read, “So touched to be appreciated and remembered. I taught at the Oakland Community School. I saw the picture of my comrades. The fight goes on. Someone told me that an Asian woman saw me in the picture of the Oakland Community School and said she was glad there was an Asian woman at the school, this was a great affirmation. Power to the people.”

“That’s how we were we wanted everybody to be involved as much as they wanted to be because we live in an exclusive world, but we weren’t like that,” Ericka said.

Many of the programs developed and operated by the Panthers are recognizable today as the government-sponsored and community programs, such as First 5 and free health care clinics, respectively, in our cities, neighborhoods, and schools, nearly 40 years after the Black Panther Party dissolved.

Creating Black Joy and Pride

During last summer’s racial reckoning and demonstrations against police brutality, Jil was seeking a positive, healing way to channel her anger following the police killings of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd.

George was murdered by former Minneapolis officer Derek Chauvin last May for allegedly buying cigarettes at a Minneapolis market using a fake $20 bill. Video of Derek’s knee on George’s neck as he called out for his mother and crying, “I can’t breathe,” went viral. Derek is currently serving 22.5 years in prison.

Breonna, a Black medical worker, was shot by police while she slept in her own bed in Louisville, Kentucky in March 2020. The police entered her home on a no-knock warrant.

Jil was unsettled, particularly by the silence surrounding Taylor’s death two and a half months before the public outcry over George’s killing.

A lifelong activist, Jil didn’t want to go out into the streets to join the outraged masses. She didn’t want to create another mural memorializing Black people who were victims of police brutality. Quarantined due to the global pandemic, she sat in her house meditating.

“I was feeling a lot of grief and a lot of rage, and [I] just kind of meditated on it,” Jil said, stating she realized she lost balance and had no joy in her life at that point.

“I said, ‘I need to find something that’s going to make me feel joyful, to make me feel seen, and to make me feel heard,'” recalled Jil who worked in the music industry prior to the global pandemic.

Walking along Broadway, one of Oakland’s main streets, Jil looked at the murals that artists painted on the boarded-up windows and sides of buildings.

“By the time I got home, I kind of looked up at my house, I said, ‘You know, I am going to put a mural on my house and it’s not going to be anything about what has been done to us. It is going to be about … what it looks like [when] … we do for ourselves,” Jil said.

She was inspired not only by the murals she saw, but by the “Say Her Name” movement and the invisibility of the women who made up 70% of the Black Panther Party.

“The women of the Black Panther Party have never been honored,” said Jil, who was born in Chicago in 1966, the year the Panthers came into existence.

Now living in the heart of where the party took root and grew for more than 15 years, it felt right to her to honor the women of the party, she said.

Ericka was immediately onboard advising her when Jil called.

The Black Panther elder reminded Jil in her warm way, “You have to have their names on the wall,” she said about the 260 known women who were Panthers.

“I’m sure that many of them have wondered when they would ever be recognized for everything that they did because it was women who sustained all of these party programs,” she said.

Jil anticipates adding more names as more women are discovered.

“People tell us they feel like it is a sacred space to them,” Ericka said.

“It really is a singular achievement,” Lisbet said about what Jil achieved with the museum and mural. “Every step along the way, it has surpassed every expectation.”

Jil simply said, “The mural is for everyone, and the museum is for everyone.”

She hopes to make the museum permanent and transform the exhibit and space into a community space.

“My ownership of the project ends at the property line and beyond that it belongs to everyone else.”

The museum is small, but it is mighty leaving an indelible impression in its recollection of an era past and its lessons for now and the future.

It is an important contribution to the American historical canon that should not be missed.

THE GAZE

The Women of the Black Panther Party Mural and Mini Black Panther Museum. West Oakland, California. 646-306-7175 (text only). . westoaklandmuralproject.org.

TYPE OF EVENT: Independent, privately owned-museum. History. American History. African American History. Black History. Women’s History. Oakland History.

RATING: 4 (0 being the worst rating and 5 being the best rating)

VIBE: Educational and community storytelling experience.

SCENE: Casual and welcoming environment, organizers are excited to teach in an accessible way.

SERVICE: Personable, warm, welcoming guides with in-depth knowledge about the Black Panther Party and women within the party. The house is inaccessible for those with mobility issues.

DAZZLE ME AGAIN: Learning about the programs and how they evolved, the commitment of the community to better themselves, and the women’s contributions to the movement was an exceptional experience.

WHERE TO NEXT?: The proprietor is attempting to make this into a permanent museum.

THE TICKET: $$ = $10 – $30 (Price of average ticket, plus service fees to enter the museum.)

WORTH THE OUTTING?: This was a rock’n good time!

Book your next adventure with Girls That Roam Travel. Contact Heather Cassell at Girls That Roam Travel at 415-517-7239 or at .

To contract an original article, purchase reprints or become a media partner, contact .