Curve Magazine’s Lesbian Cartoonists Are in the Spotlight at New Retrospective Exhibit in San Francisco

by Heather Cassell

Before lesbian cartoonist Alison Bechdel made it on Broadway with her autobiographical musical, “Fun Home,” there was Curve magazine.

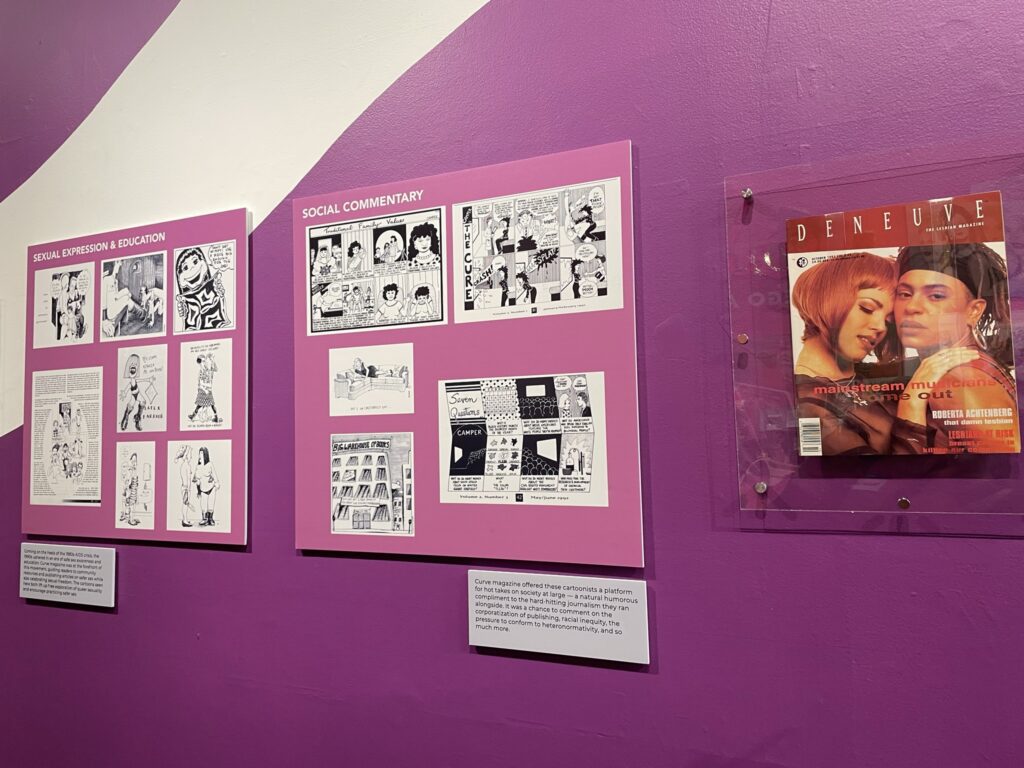

The glossy lesbian magazine, Deneuve, launched by publisher Frances “Franco” Stevens in 1990 became the home for many lesbian cartoonists’ comics and illustrations that brought the articles to life on the pages.

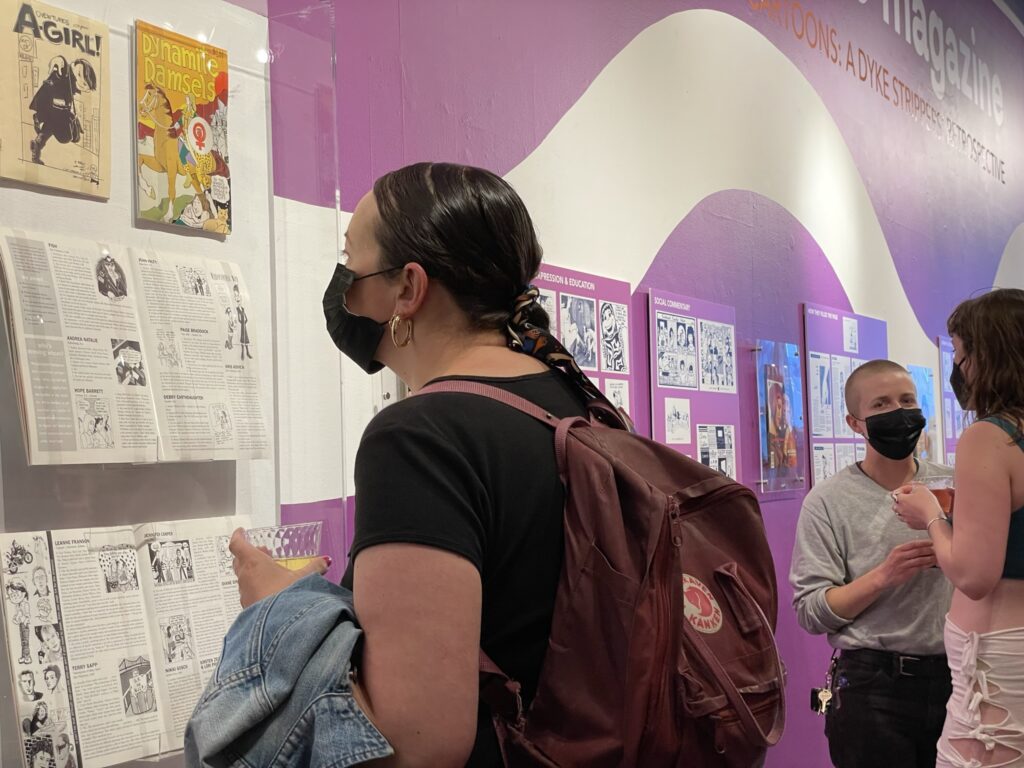

More than three decades later, those drawings by 14 artists have been taken out of the vault. They are now on display in the “Curve Magazine Cartoons: A Dyke Strippers’ Retrospective” exhibit at the GLBT Historical Society in San Francisco’s Castro District.

Attendees got a first look at Alison’s works along with Diane DiMassa, creator of “Hothead Paisan, Homicidal Lesbian Terrorist;” and the late Kris Kovick, and others on display at the museum.

Franco, her wife, Jen Ranin; the exhibit curator Julia Rosenzweig, some of the cartoonists, and about 40 longtime fans of the magazine and some who are part of a new generation came out to the opening reception of the exhibit in San Francisco’s Castro District July 13.

The magazine changed its name to Curve in 1996, which also was the year the magazine started seeing less of lesbian cartoonists’ works in its pages as the turn of the century neared. By 2000, the illustrations disappeared from Curve’s pages.

Curve was sold to Australia-based Avalon CEO Silke Bader, which also published Lesbians on the Loose, better known as LOTL, in 2010. Franco bought Curve back from Silke in 2021. The magazine ceased publishing that same year. Instead, Franco and Jen, who is also the director and co-producer of “Ahead of the Curve,” co-founded The Curve Foundation to continue Curve’s mission to “addresses queer woman’s past, present, and future,” Jen told exhibit attendees after giving Franco a big smooch on the lips and fawning over her “hot wife.”

“Ahead of the Curve” is a documentary that tells the story of the early days of Franco’s founding of Curve magazine and its explosion into a cultural phenomenon.

The foundation’s mission is to digitize and preserve Curve magazine through similar exhibits, support queer women in journalism, and continue to tell queer women’s and gender-diverse people’s stories.

I was there in the early days as Curve’s office intern editing the pages the very cartoons illustrated among other tasks in the magazine’s San Francisco offices. It was a groundbreaking, sexy, and revolutionary time in San Francisco’s “Gay ‘90s.” Curve was “lesbian chic” long before HBO’s “Sex and the City” tackled “Power Dykes and lesbian relationships,” bisexuals, and gender-bending, and Showtime brought lesbian lives into living rooms across North America with “The L Word.” Seeing the cartoons and Franco again brought back those heady days of my 20s and working at the magazine.

I also documented the sale and buyback of Curve for the Bay Area Reporter in more recent decades.

Bisexual sexpert Carol Queen of the groundbreaking women-founded sex shop, Good Vibrations, which sponsored the reception, expressed to the exhibit attendees how relevant Curve was in giving visibility to queer women when queer women were so hidden you had to know where to find them before the magazine.

“There was a time when we weren’t visible or we were only visible if you knew where to go and you were fortunate enough to be able to get there,” said Carol recalling the days before Curve magazine showed up on the San Francisco sex shop’s magazine rack. Profound changes started to happen, “and Curve was part of that.”

“Curve filled a niche that had not been filled before,” she told exhibit attendees. Curve was “frisky and fun, at the same time they were serious about what they wanted to put out in the world about us.”

Dyke’s Drawing

Julia, who curated the exhibit and is also the foundation’s archivist and outreach manager, recounted meeting nine of the 14 artists whose works are displayed in the exhibit. The artists expressed a “sense of humor,” “amusement,” and some “angst about aging” knowing “that their 30-year-old cartoons are being showcased at the museum,” she told reception attendees.

Cartoons displayed in the exhibit from 1991 to 2000 include works by Alison, Diane, Kris, Hope Barrett, Paige Braddock, Jennifer Camper, Cari Campbell, Rhonda Dicksion, Debby Earthdaughter, Fish, Roberta Gregory, Joan Hilty, Andrea Natalie, and Elizabeth Watasin.

“Mostly, there was a lot of appreciation, because most of these artists had nowhere to publish these cartoons,” she said. “They couldn’t reflect their diverse sexual and gender identities because mainstream publications at the time would be censored if they published those types of things.”

While the artists might have wanted to draw a similar path as the famous author and cartoonist of the beloved comic strip, “Dykes to Watch Out For,” Alison remains a breakout dyke cartoonist. “Dykes to Watch Out For” made it due to her own elbow grease self-syndicating the comic strip which ran in nearly every LGBTQ newspaper and magazine from 1983 to 2008. Her cartoons also made it into the pages of The New Yorker, Slate, McSweeney’s, The New York Times Book Review, and Granta, according to her biography on the “Dykes to Watch Out For” website. Her autobiographical story, “Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic,” was adapted for Broadway and nabbed her five Tony Awards, including “Best Musical,” in 2015. She’s gone on to write two more books, a 2012 memoir “Are You My Mother? A Comic Drama” and “The Secret to Superhuman Strength” published in 2021.

Julia explained that the artists had “low expectations for the reach that these cartoons could have,” until Curve hit the scene. “Which is why it is so special to be able to show them here.”

“Within the first few issues of Deneuve (now Curve magazine), I noticed these wonderful expressive cartoons peppered throughout the pages,” said Julia who was struck by the cartoons when she first started reviewing the first few issues of Deneuve magazine. “They were just so fun and cheeky and political, and just so gay.”

“It was so unapologetically lesbian,” she continued stating she is hoping the exhibit portrays the spirit of the decade. “They’re just a perfect way to accurately document both lesbian culture and the 90s.”

Curve’s covers and pages depicted San Francisco and the country’s diverse lesbian community, but that diversity did not translate to the cartoonists who illustrated its pages, Alison noted in Deneuve’s October 1994 article titled “Dyke Strippers.”

Alison is quoted from the article in the introduction to “Curve Magazine Cartoons: A Dyke Strippers’ Retrospective” exhibit, “The artists Deneuve has gathered here come from zines and newspapers. They create strips, single-panel cartoons, and longer graphic narratives. Some have had collections of their work published, others have self-published. Their subject matter covers, among other things, disabled lesbians, girljocks, leatherdykes, bisexuals, and homicidal terrorists—but there’s room for more diversity. Unfortunately, the work you see here reflects the overwhelming whiteness of the field. I look forward to more women of color cartoonists drawing from their experiences and adding their crucial perspectives to this rich, graphic history.”

Julia agreed pointing out that it wasn’t because there was a lack of queer Black, brown, indigenous, and people of color cartoonists at the time. To tie the cartoons to today’s audience, she leveled the playing field combing the GLBT Historical Society’s archives for cartoons created by queer women and nonbinary BIPOC for the exhibit, she told the audience.

The exhibit covers the very radically sexy, political, feminist lesbian cartoons that examined culture and art and made social commentary about issues at the time, such as sexual expression and education about safer sex (HIV/AIDS was still a crisis). The works poke fun at lesbian culture from queer women’s love of sports to their hair styles to sharing their emotions and more, on the labels next to panels exploring “Lesbian Culture,” “Social Commentary,” “Sexual Expression,” and the physical design of the magazine.

Curve’s Importance, Then And Now

Franco couldn’t imagine how relevant and important the magazine would be to the queer women’s community then, and more than three decades later.

“When Jen started making the movie ‘Ahead of the Curve,’ which chronologize my journey to make Curve magazine along with all the other women whose blood, sweat, and tears literally went into making the magazine, we realized that we have a lot of people to represent. We knew we couldn’t represent all of them, but if you would have told us that 32 years later this magazine would still be making such an impact on the community, none of us would have believed it. It’s really astonishing. In fact, I’m getting a little emotional over it,” Franco said wiping away a tear from her eye as her voice cracked.

Franco continued stating that during the creation of the documentary Jen and she realized that while Curve “was important” the mission behind the magazine was really driving it.

Jen stepped in handing Franco a tissue. She explained that Curve represented not only the history of the dyke comics whose artwork appeared in the magazine’s pages, but also the journalists who wrote the stories about lesbian, queer women, and nonbinary people’s lives that appeared in the pages between the glossy cover for more than 30 years.

“We lift up our past through the Curve archive which is 30 years of Curve magazine,” Jen said. “We champion the present culture makers through the Curve digital edition that will address the issues that are coming out now on our site.”

“We’re looking at what’s happening today with journalism, with queer culture,” she added. “It’s sexy as hell.”

The attendees laughed.

Jen explained that foundation working with the National Gay and Lesbian Journalist Association honoring queer women journalists past and present with the Curve Excellence in Journalism Awards and the Curve Award for Emerging Journalists.

She recalled how the foundation helped two young queer journalists through the emerging journalists award. Reema Khrais created a podcast, “This Is Uncomfortable,” and another reporter who wanted to broaden her reach and break into bigger markets was recently published in the New York Times.

“It is having the support of every member of our community that makes a powerful statement,” Jen said in her pitch to support the foundation’s work. “It gives us the momentum we need to continue doing the work that we need to do to keep our community vital and visible.”

Franco, Jen, and Julia invited attendees to enjoy the exhibit which is on display now through October 2023.

Curve’s cartoons – those on display at the exhibit and the entire collection, including those that didn’t make it into the show – can be found at the digital Curve archive.

“I hope it makes you laugh,” Julia said. “I hope it inspires you to reflect on the history of lesbian representation in media.”

The “Curve Magazine Cartoons: A Dyke Strippers’ Retrospective” is open now through October at the GLBT Historical Society Museum, 4127 18th Street, in San Francisco. Donate to The Curve Foundation. Read Curve online.

To purchase reprints of this or other articles or contract an original article, contact .